The first nuclear weapons, though large, cumbersome and inefficient, provided the basic design building blocks of all future weapons. Here the

Gadget device is prepared for the first

nuclear test:

Trinity.

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package

[1] of a

nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three basic design types. In all three, the explosive energy of deployed devices has been derived primarily from

nuclear fission, not

fusion.

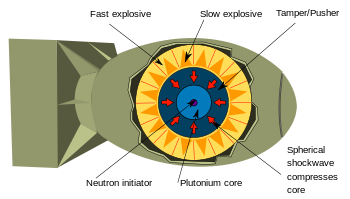

- Pure fission weapons were the first nuclear weapons built and have so far been the only type ever used in warfare. The active material is fissile uranium (U-235) or plutonium (Pu-239), explosively assembled into a chain-reacting critical mass by one of two methods:

- Gun assembly: one piece of fissile uranium is fired at a fissile uranium target at the end of the weapon, similar to firing a bullet down a gun barrel, achieving critical mass when combined.

- Implosion: a fissile mass of either material (U-235, Pu-239, or a combination) is surrounded by high explosives that compress the mass, resulting in criticality.

- The implosion method can use either uranium or plutonium as fuel. The gun method only uses uranium. Plutonium is considered impractical for the gun method because of early triggering due to Pu-240 contamination and due to its time constant for prompt critical fission being much shorter than that of U-235.

- Fusion-boosted fission weapons improve on the implosion design. The high pressure and temperature environment at the center of an exploding fission weapon compresses and heats a mixture of tritium and deuterium gas (heavy isotopes of hydrogen). The hydrogen fuses to form helium and free neutrons. The energy release from this fusion reaction is relatively negligible, but each neutron starts a new fission chain reaction, speeding up the fission and greatly reducing the amount of fissile material that would otherwise be wasted when expansion of the fissile material stops the chain reaction. Boosting can more than double the weapon's fission energy release.

- Two-stage thermonuclear weapons are essentially a chain of fission-boosted fusion weapons (not to be confused with the previously mentioned fusion-boosted fission weapons), usually with only two stages in the chain. The second stage, called the "secondary," is imploded by x-ray energy from the first stage, called the "primary." This radiation implosion is much more effective than the high-explosive implosion of the primary. Consequently, the secondary can be many times more powerful than the primary, without being bigger. The secondary can be designed to maximize fusion energy release, but in most designs fusion is employed only to drive or enhance fission, as it is in the primary. More stages could be added, but the result would be a multi-megaton weapon too powerful to serve any plausible purpose.[2] (The United States briefly deployed a three-stage 25-megaton bomb, the B41, starting in 1961. Also in 1961, the Soviet Union tested, but did not deploy, a three-stage 50–100 megaton device, Tsar Bomba.)

Pure fission weapons historically have been the first type to be built by a nation state. Large industrial states with well-developed nuclear arsenals have two-stage thermonuclear weapons, which are the most compact, scalable, and cost effective option once the necessary industrial infrastructure is built.

Most known innovations in nuclear weapon design originated in the United States, although some were later developed independently by other states;

[3] the following descriptions feature U.S. designs.

In early news accounts, pure fission weapons were called atomic bombs or A-bombs, a misnomer since the energy comes only from the nucleus of the atom. Weapons involving fusion were called hydrogen bombs or H-bombs, also a misnomer since their destructive energy comes mostly from fission. Insiders favored the terms nuclear and thermonuclear, respectively.

The term thermonuclear refers to the high temperatures required to initiate fusion. It ignores the equally important factor of pressure, which was considered secret at the time the term became current. Many nuclear weapon terms are similarly inaccurate because of their origin in a classified environment.

[edit] Nuclear reactions

Nuclear fission splits heavier atoms to form lighter atoms. Nuclear fusion bonds together lighter atoms to form heavier atoms. Both reactions generate roughly a million times more energy than comparable chemical reactions, making nuclear bombs a million times more powerful than non-nuclear bombs, which a French patent claimed in May 1939.

[4]

In some ways, fission and fusion are opposite and complementary reactions, but the particulars are unique for each. To understand how nuclear weapons are designed, it is useful to know the important similarities and differences between fission and fusion. The following explanation uses rounded numbers and approximations.

[5]

[edit] Fission

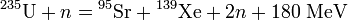

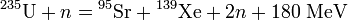

When a free neutron hits the nucleus of a fissionable atom like uranium-235 (

235U), the uranium splits into two smaller atoms called fission fragments, plus more neutrons. Fission can be self-sustaining because it produces more neutrons of the speed required to cause new fissions.

The uranium atom can split any one of dozens of different ways, as long as the atomic weights add up to 236 (uranium plus the extra neutron). The following equation shows one possible split, namely into

strontium-95 (

95Sr),

xenon-139 (

139Xe), and two neutrons (n), plus energy:

[6]

-

-

The immediate energy release per atom is 180 million

electron volts (MeV), i.e. 74 TJ/kg, of which 90% is kinetic energy (or motion) of the fission fragments, flying away from each other mutually repelled by the positive charge of their protons (38 for strontium, 54 for xenon). Thus their initial kinetic energy is 67 TJ/kg, hence their initial speed is 12,000 kilometers per second, but their high electric charge causes many inelastic collisions with nearby nuclei. The fragments remain trapped inside the bomb's uranium pit until their motion is converted into x-ray heat, a process which takes about a millionth of a second (a microsecond).

This x-ray energy produces the blast and fire which are normally the purpose of a nuclear explosion.

After the fission products slow down, they remain radioactive. Being new elements with too many neutrons, they eventually become stable by means of beta decay, converting neutrons into protons by throwing off electrons and gamma rays. Each fission product nucleus decays between one and six times, average three times, producing a variety of isotopes of different elements, some stable, some highly radioactive, and others radioactive with half-lives up to 200,000 years.

[7] In reactors, the radioactive products are the nuclear waste in spent fuel. In bombs, they become radioactive fallout, both local and global.

Meanwhile, inside the exploding bomb, the free neutrons released by fission strike nearby U-235 nuclei causing them to fission in an exponentially growing chain reaction (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, etc.). Starting from one, the number of fissions can theoretically double a hundred times in a microsecond, which could consume all uranium up to hundreds of tons by the hundredth link in the chain. In practice, bombs do not contain that much uranium, and, anyway, just a few kilograms undergo fission before the uranium blows itself apart.

Holding an exploding bomb together is the greatest challenge of fission weapon design. The heat of fission rapidly expands the uranium pit, spreading apart the target nuclei and making space for the neutrons to escape without being captured. The chain reaction stops.

Materials which can sustain a chain reaction are called

fissile. The two fissile materials used in nuclear weapons are: U-235, also known as

highly enriched uranium (HEU), oralloy (Oy) meaning Oak Ridge Alloy, or 25 (the last digits of the atomic number, which is 92 for uranium, and the atomic weight, here 235, respectively); and Pu-239, also known as plutonium, or 49 (from 94 and 239).

Uranium's most common isotope, U-238, is fissionable but not fissile (meaning that it cannot sustain a chain reaction by itself but can be made to fission, specifically by neutrons from a fusion reaction). Its aliases include natural or unenriched uranium,

depleted uranium (DU), tubealloy (Tu), and 28. It cannot sustain a chain reaction, because its own fission neutrons are not powerful enough to cause more U-238 fission. However, the neutrons released by

fusion will fission U-238. This U-238 fission reaction produces most of the destructive energy in a typical two-stage thermonuclear weapon.

[edit] Fusion

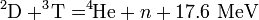

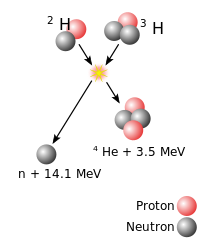

Fusion produces neutrons which dissipate energy from the reaction.

[8] In weapons, the most important fusion reaction is called the D-T reaction. Using the heat and pressure of fission, hydrogen-2, or deuterium (

2D), fuses with hydrogen-3, or tritium (

3T), to form helium-4 (

4He) plus one neutron (n) and energy:

[9]

-

-

Notice that the total energy output, 17.6 MeV, is one tenth of that with fission, but the ingredients are only one-fiftieth as massive, so the energy output per unit mass is greater. However, in this fusion reaction 80% of the energy, or 14 MeV, is in the motion of the neutron which, having no electric charge and being almost as massive as the hydrogen nuclei that created it, can escape the scene without leaving its energy behind to help sustain the reaction – or to generate x-rays for blast and fire.

The only practical way to capture most of the fusion energy is to trap the neutrons inside a massive bottle of heavy material such as lead, uranium, or plutonium. If the 14 MeV neutron is captured by uranium (either type: 235 or 238) or plutonium, the result is fission and the release of 180 MeV of fission energy, multiplying the energy output tenfold.

Fission is thus necessary to start fusion, helps to sustain fusion, and captures and multiplies the energy released in fusion neutrons. In the case of a neutron bomb (see below) the last-mentioned does not apply since the escape of neutrons is the objective.

[edit] Tritium production

A third important nuclear reaction is the one that creates

tritium, essential to the type of fusion used in weapons and, incidentally, the most expensive ingredient in any nuclear weapon. Tritium, or hydrogen-3, is made by bombarding

lithium-6 (

6Li) with a

neutron (n) to produce

helium-4 (

4He) plus tritium (

3T) and energy:

[9]

-

-

A nuclear reactor is necessary to provide the neutrons. The industrial-scale conversion of lithium-6 to tritium is very similar to the conversion of uranium-238 into plutonium-239. In both cases the feed material is placed inside a nuclear reactor and removed for processing after a period of time. In the 1950s, when reactor capacity was limited, the production of tritium and plutonium were in direct competition. Every atom of tritium in a weapon replaced an atom of plutonium that could have been produced instead.

The fission of one plutonium atom releases ten times more total energy than the fusion of one tritium atom, and it generates fifty times

[citation needed] more blast and fire. For this reason, tritium is included in nuclear weapon components only when it causes more fission than its production sacrifices, namely in the case of fusion-boosted fission.

However, an exploding nuclear bomb is a nuclear reactor. The above reaction can take place simultaneously throughout the secondary of a two-stage thermonuclear weapon, producing tritium in place as the device explodes.

Of the three basic types of nuclear weapon, the first, pure fission, uses the first of the three nuclear reactions above. The second, fusion-boosted fission, uses the first two. The third, two-stage thermonuclear, uses all three.

[edit] Pure fission weapons

The first task of a nuclear weapon design is to rapidly assemble a

supercritical mass of fissile uranium or plutonium. A supercritical mass is one in which the percentage of fission-produced neutrons captured by another fissile nucleus is large enough that each fission event, on average, causes more than one additional fission event.

Once the critical mass is assembled, at maximum density, a burst of neutrons is supplied to start as many chain reactions as possible. Early weapons used an "

urchin" inside the pit containing

polonium-210 and

beryllium separated by a thin barrier. Implosion of the pit crushed the urchin, mixing the two metals, thereby allowing alpha particles from the polonium to interact with beryllium to produce free neutrons. In modern weapons, the neutron generator is a high-voltage vacuum tube containing a

particle accelerator which bombards a deuterium/tritium-metal hydride target with deuterium and tritium

ions. The resulting

small-scale fusion produces neutrons at a protected location outside the physics package, from which they penetrate the pit. This method allows better control of the timing of chain reaction initiation.

The critical mass of an uncompressed sphere of bare metal is 110 lb (50 kg) for uranium-235 and 35 lb (16 kg) for delta-phase plutonium-239. In practical applications, the amount of material required for criticallity is modified by shape, purity, density, and the proximity to

neutron-reflecting material, all of which affect the escape or capture of neutrons.

To avoid a chain reaction during handling, the fissile material in the weapon must be sub-critical before detonation. It may consist of one or more components containing less than one uncompressed critical mass each. A thin hollow shell can have more than the bare-sphere critical mass, as can a cylinder, which can be arbitrarily long without ever reaching criticallity.

A

tamper is an optional layer of dense material surrounding the fissile material. Due to its

inertia it delays the expansion of the reacting material, increasing the efficiency of the weapon. Often the same layer serves both as tamper and as neutron reflector.

[edit] Gun-type assembly weapon

Diagram of a gun-type fission weapon

Little Boy, the Hiroshima bomb, used 141 lb (64 kg) of uranium with an average enrichment of around 80%, or 112 lb (51 kg) of U-235, just about the bare-metal critical mass. (See

Little Boy article for a detailed drawing.) When assembled inside its tamper/reflector of

tungsten carbide, the 141 lb (64 kg) was more than twice critical mass. Before the detonation, the uranium-235 was formed into two sub-critical pieces, one of which was later fired down a gun barrel to join the other, starting the atomic explosion. About 1% of the uranium underwent fission;

[10] the remainder, representing most of the entire wartime output of the giant factories at Oak Ridge, scattered uselessly.

[11] The half life of uranium-235 is 704 million years.

The inefficiency was caused by the speed with which the uncompressed fissioning uranium expanded and became sub-critical by virtue of decreased density. Despite its inefficiency, this design, because of its shape, was adapted for use in small-diameter, cylindrical artillery shells (a

gun-type warhead fired from the barrel of a much larger gun). Such warheads were deployed by the United States until 1992, accounting for a significant fraction of the U-235 in the arsenal, and were some of the first weapons dismantled to comply with treaties limiting warhead numbers. The rationale for this decision was undoubtedly a combination of the lower yield and grave safety issues associated with the gun-type design.

[edit] Implosion-type weapon

Fat Man, the Nagasaki bomb, used 13.6 lb (6.2 kg, about 12 fluid ounces or 350 ml in volume) of Pu-239, which is only 39% of bare-sphere critical mass. (See

Fat Man article for a detailed drawing.) Surrounded by a U-238 reflector/tamper, the pit was brought close to critical mass by the neutron-reflecting properties of the U-238. During detonation, criticality was achieved by implosion. The plutonium pit was squeezed to increase its density by simultaneous detonation of the conventional explosives placed uniformly around the pit. The explosives were detonated by multiple

exploding-bridgewire detonators. It is estimated that only about 20% of the plutonium underwent fission; the rest, about 11 lb (5.0 kg), was scattered.

An implosion shock wave might be of such short duration that only a fraction of the pit is compressed at any instant as the wave passes through it.

Flash X-Ray images of the converging shock waves formed during a test of the high explosive lens system.

A pusher shell made out of low

density metal—such as

aluminum,

beryllium, or an

alloy of the two metals (aluminum being easier and safer to shape, and is two orders of magnitude cheaper; beryllium for its high-neutron-reflective capability) —may be needed. The pusher is located between the explosive lens and the tamper. It works by reflecting some of the shock wave backwards, thereby having the effect of lengthening its duration. Fat Man used an aluminum pusher.

The key to Fat Man's greater efficiency was the inward momentum of the massive U-238 tamper (which did not undergo fission). Once the chain reaction started in the plutonium, the momentum of the implosion had to be reversed before expansion could stop the fission. By holding everything together for a few hundred nanoseconds more, the efficiency was increased.

[edit] Plutonium pit

The core of an implosion weapon – the fissile material and any reflector or tamper bonded to it – is known as the

pit. Some weapons tested during the 1950s used pits made with

U-235 alone, or in

composite with

plutonium,

[12] but all-plutonium pits are the smallest in diameter and have been the standard since the early 1960s.

Casting and then machining plutonium is difficult not only because of its toxicity, but also because plutonium has many different

metallic phases, also known as

allotropes. As plutonium cools, changes in phase result in distortion and cracking. This distortion is normally overcome by alloying it with 3–3.5 molar% (0.9–1.0% by weight)

gallium, forming a

plutonium-gallium alloy, which causes it to take up its delta phase over a wide temperature range.

[13] When cooling from molten it then suffers only a single phase change, from epsilon to delta, instead of the four changes it would otherwise pass through. Other

trivalent metals would also work, but gallium has a small neutron

absorption cross section and helps protect the plutonium against

corrosion. A drawback is that gallium compounds themselves are corrosive and so if the plutonium is recovered from dismantled weapons for conversion to

plutonium dioxide for

power reactors, there is the difficulty of removing the gallium.

Because plutonium is chemically reactive it is common to plate the completed pit with a thin layer of inert metal, which also reduces the toxic hazard.

[14] The gadget used galvanic silver plating; afterwards,

nickel deposited from

nickel tetracarbonyl vapors was used,

[14] but

gold is now preferred.

[citation needed]

[edit] Levitated-pit implosion

The first improvement on the Fat Man design was to put an air space between the tamper and the pit to create a hammer-on-nail impact. The pit, supported on a hollow cone inside the tamper cavity, was said to be levitated. The three tests of

Operation Sandstone, in 1948, used Fat Man designs with levitated pits. The largest yield was 49 kilotons, more than twice the yield of the unlevitated Fat Man.

[15]

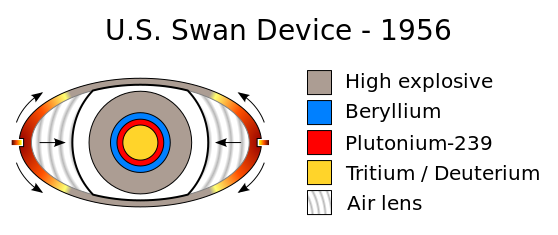

It was immediately clear that implosion was the best design for a fission weapon. Its only drawback seemed to be its diameter. Fat Man was 5 feet (1.5 m) wide vs 2 feet (60 cm) for Little Boy.

Eleven years later, implosion designs had advanced sufficiently that the 5-foot (1.5 m)-diameter sphere of Fat Man had been reduced to a 1-foot (0.30 m)-diameter cylinder 2 feet (0.61 m) long, the

Swan device.

The Pu-239 pit of Fat Man was only 3.6 inches (9 cm) in diameter, the size of a softball. The bulk of Fat Man's girth was the implosion mechanism, namely concentric layers of U-238, aluminum, and high explosives. The key to reducing that girth was the two-point implosion design.

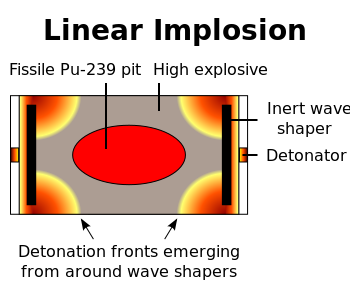

[edit] Two-point linear implosion

A very inefficient implosion design is one that simply reshapes an ovoid into a sphere, with minimal compression. In linear implosion, an untamped, solid, elongated mass of Pu-239, larger than critical mass in a sphere, is embedded inside a cylinder of high explosive with a detonator at each end.

[16]

Detonation makes the pit critical by driving the ends inward, creating a spherical shape. The shock may also change plutonium from delta to alpha phase, increasing its density by 23%, but without the inward momentum of a true implosion. The lack of compression makes it inefficient, but the simplicity and small diameter make it suitable for use in artillery shells and atomic demolition munitions – ADMs – also known as backpack or

suitcase nukes.

All such low-yield battlefield weapons, whether gun-type U-235 designs or linear implosion Pu-239 designs, pay a high price in fissile material in order to achieve diameters between six and ten inches (254 mm).

[edit] Two-point hollow-pit implosion

A more efficient two-point implosion system uses two high explosive lenses and a hollow pit.

A hollow plutonium pit was the original plan for the 1945 Fat Man bomb, but there was not enough time to develop and test the implosion system for it. A simpler solid-pit design was considered more reliable, given the time restraint, but it required a heavy U-238 tamper, a thick aluminum pusher, and three tons of high explosives.

After the war, interest in the hollow pit design was revived. Its obvious advantage is that a hollow shell of plutonium, shock-deformed and driven inward toward its empty center, would carry momentum into its violent assembly as a solid sphere. It would be self-tamping, requiring a smaller U-238 tamper, no aluminum pusher and less high explosive.

The Fat Man bomb had two concentric, spherical shells of high explosives, each about 10 inches (25 cm) thick. The inner shell drove the implosion. The outer shell consisted of a

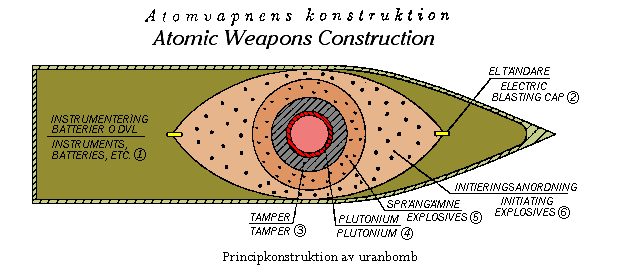

soccer-ball pattern of 32 high explosive lenses, each of which converted the convex wave from its detonator into a concave wave matching the contour of the outer surface of the inner shell. If these 32 lenses could be replaced with only two, the high explosive sphere could become an ellipsoid (prolate spheroid) with a much smaller diameter.

A good illustration of these two features is a 1956 drawing from the

Swedish nuclear weapon program (which was terminated before it produced a test explosion). The drawing shows the essential elements of the two-point hollow-pit design.

There are similar drawings in the open literature that come from the post-war German nuclear bomb program, which was also terminated, and from the French program, which produced an arsenal.

The mechanism of the high explosive lens (diagram item #6) is not shown in the Swedish drawing, but a standard lens made of fast and slow high explosives, as in Fat Man, would be much longer than the shape depicted. For a single high explosive lens to generate a concave wave that envelops an entire hemisphere, it must either be very long or the part of the wave on a direct line from the detonator to the pit must be slowed dramatically.

A slow high explosive is too fast, but the flying plate of an "air lens" is not. A metal plate, shock-deformed, and pushed across an empty space can be designed to move slowly enough.

[17][18] A two-point implosion system using air lens technology can have a length no more than twice its diameter, as in the Swedish diagram above.

[edit] Fusion-boosted fission weapons

The next step in miniaturization was to speed up the fissioning of the pit to reduce the minimum inertial confinement time. The hollow pit provided an ideal location to introduce fusion for the boosting of fission. A 50–50 mixture of tritium and deuterium gas, pumped into the pit during arming, will fuse into helium and release free neutrons soon after fission begins. The neutrons will start a large number of new chain reactions while the pit is still critical or nearly critical.

Once the hollow pit is perfected, there is little reason not to boost.

The concept of fusion-boosted fission was first tested on May 25, 1951, in the

Item shot of

Operation Greenhouse,

Eniwetok, yield 45.5 kilotons.

Boosting reduces diameter in three ways, all the result of faster fission:

- Since the compressed pit does not need to be held together as long, the massive U-238 tamper can be replaced by a light-weight beryllium shell (to reflect escaping neutrons back into the pit). The diameter is reduced.

- The mass of the pit can be reduced by half, without reducing yield. Diameter is reduced again.

- Since the mass of the metal being imploded (tamper plus pit) is reduced, a smaller charge of high explosive is needed, reducing diameter even further.

Since boosting is required to attain full design yield, any reduction in boosting reduces yield. Boosted weapons are thus

variable-yield weapons. Yield can be reduced any time before detonation, simply by putting less than the full amount of tritium into the pit during the arming procedure.

The first device whose dimensions suggest employment of all these features (two-point, hollow-pit, fusion-boosted implosion) was the Swan device, tested June 22, 1956, as the Inca shot of

Operation Redwing, at Eniwetok. Its yield was 15 kilotons, about the same as Little Boy, the Hiroshima bomb. It weighed 105 lb (47.6 kg) and was cylindrical in shape, 11.6 inches (29.5 cm) in diameter and 22.9 inches (58 cm) long. The above schematic illustrates what were probably its essential features.

Eleven days later, July 3, 1956, the Swan was test-fired again at Eniwetok, as the Mohawk shot of Redwing. This time it served as the primary, or first stage, of a two-stage thermonuclear device, a role it played in a dozen such tests during the 1950s. Swan was the first off-the-shelf, multi-use primary, and the prototype for all that followed.

After the success of Swan, 11 or 12 inches (300 mm) seemed to become the standard diameter of boosted single-stage devices tested during the 1950s. Length was usually twice the diameter, but one such device, which became the

W54 warhead, was closer to a sphere, only 15 inches (380 mm) long. It was tested two dozen times in the 1957–62 period before being deployed. No other design had such a long string of test failures. Since the longer devices tended to work correctly on the first try, there must have been some difficulty in flattening the two high explosive lenses enough to achieve the desired length-to-width ratio.

One of the applications of the W54 was the

Davy Crockett XM-388 recoilless rifle projectile, shown here in comparison to its Fat Man predecessor, dimensions in inches.

Another benefit of boosting, in addition to making weapons smaller, lighter, and with less fissile material for a given yield, is that it renders weapons immune to radiation interference (RI). It was discovered in the mid-1950s that plutonium pits would be particularly susceptible to partial predetonation if exposed to the intense radiation of a nearby nuclear explosion (electronics might also be damaged, but this was a separate issue). RI was a particular problem before effective

early warning radar systems because a first strike attack might make retaliatory weapons useless. Boosting reduces the amount of plutonium needed in a weapon to below the quantity which would be vulnerable to this effect.

[edit] Two-stage thermonuclear weapons

Pure fission or fusion-boosted fission weapons can be made to yield hundreds of kilotons, at great expense in fissile material and tritium, but by far the most efficient way to increase nuclear weapon yield beyond ten or so kilotons is to tack on a second independent stage, called a secondary.

Ivy Mike, the first two-stage thermonuclear detonation, 10.4 megatons, November 1, 1952.

In the 1940s, bomb designers at

Los Alamos thought the secondary would be a canister of deuterium in liquified or hydride form. The fusion reaction would be D-D, harder to achieve than D-T, but more affordable. A fission bomb at one end would shock-compress and heat the near end, and fusion would propagate through the canister to the far end. Mathematical simulations showed it wouldn't work, even with large amounts of prohibitively expensive tritium added in.

The entire fusion fuel canister would need to be enveloped by fission energy, to both compress and heat it, as with the booster charge in a boosted primary. The design breakthrough came in January 1951, when

Edward Teller and

Stanisław Ulam invented radiation implosion—for nearly three decades known publicly only as the

Teller-Ulam H-bomb secret.

The concept of radiation implosion was first tested on May 9, 1951, in the George shot of

Operation Greenhouse, Eniwetok, yield 225 kilotons. The first full test was on November 1, 1952, the

Mike shot of

Operation Ivy, Eniwetok, yield 10.4 megatons.

In radiation implosion, the burst of X-ray energy coming from an exploding primary is captured and contained within an opaque-walled radiation channel which surrounds the nuclear energy components of the secondary. The radiation quickly turns the plastic foam that had been filling the channel into a plasma which is mostly transparent to X-rays, and the radiation is absorbed in the outermost layers of the pusher/tamper surrounding the secondary, which ablates and applies a massive force

[19] (much like an inside out rocket engine) causing the fusion fuel capsule to implode much like the pit of the primary. As the secondary implodes a fissile "spark plug" at its center ignites and provides heat which enables the fusion fuel to ignite as well. The fission and fusion chain reactions exchange neutrons with each other and boost the efficiency of both reactions. The greater implosive force, enhanced efficiency of the fissile "spark plug" due to boosting via fusion neutrons, and the fusion explosion itself provides significantly greater explosive yield from the secondary despite often not being much larger than the primary.

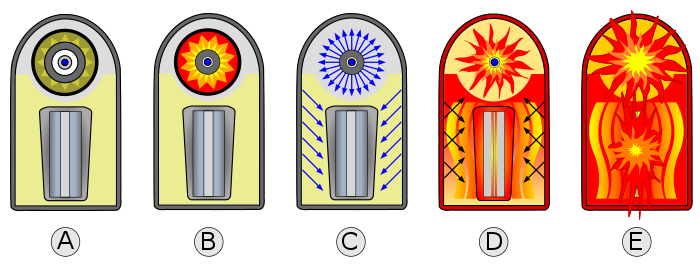

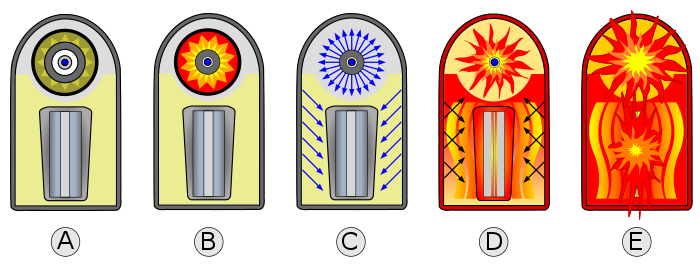

A Warhead before firing; primary at top, secondary at bottom. Both components are fusion-boosted

fission bombs.

B High-explosive fires in primary, compressing plutonium core into supercriticality and beginning a fission reaction.

C Fission in primary emits X-rays which channel along the inside of the casing, irradiating the polystyrene foam channel filler.

D Secondary compressed by X-ray induced

ablation, and Plutonium sparkplug inside the secondary begins to fission, supplying heat.

E Compressed and heated, lithium-6 deuteride fuel begins fusion reaction, neutron flux causes tamper to fission. A fireball is starting to form...

For example, for the Redwing Mohawk test on July 3, 1956, a secondary called the Flute was attached to the Swan primary. The Flute was 15 inches (38 cm) in diameter and 23.4 inches (59 cm) long, about the size of the Swan. But it weighed ten times as much and yielded 24 times as much energy (355 kilotons, vs 15 kilotons).

Equally important, the active ingredients in the Flute probably cost no more than those in the Swan. Most of the fission came from cheap U-238, and the tritium was manufactured in place during the explosion. Only the spark plug at the axis of the secondary needed to be fissile.

A spherical secondary can achieve higher implosion densities than a cylindrical secondary, because spherical implosion pushes in from all directions toward the same spot. However, in warheads yielding more than one megaton, the diameter of a spherical secondary would be too large for most applications. A cylindrical secondary is necessary in such cases. The small, cone-shaped re-entry vehicles in multiple-warhead ballistic missiles after 1970 tended to have warheads with spherical secondaries, and yields of a few hundred kilotons.

As with boosting, the advantages of the two-stage thermonuclear design are so great that there is little incentive not to use it, once a nation has mastered the technology.

In engineering terms, radiation implosion allows for the exploitation of several known features of nuclear bomb materials which heretofore had eluded practical application. For example:

- The best way to store deuterium in a reasonably dense state is to chemically bond it with lithium, as lithium deuteride. But the lithium-6 isotope is also the raw material for tritium production, and an exploding bomb is a nuclear reactor. Radiation implosion will hold everything together long enough to permit the complete conversion of lithium-6 into tritium, while the bomb explodes. So the bonding agent for deuterium permits use of the D-T fusion reaction without any pre-manufactured tritium being stored in the secondary. The tritium production constraint disappears.

- For the secondary to be imploded by the hot, radiation-induced plasma surrounding it, it must remain cool for the first microsecond, i.e., it must be encased in a massive radiation (heat) shield. The shield's massiveness allows it to double as a tamper, adding momentum and duration to the implosion. No material is better suited for both of these jobs than ordinary, cheap uranium-238, which also happens to undergo fission when struck by the neutrons produced by D-T fusion. This casing, called the pusher, thus has three jobs: to keep the secondary cool, to hold it, inertially, in a highly compressed state, and, finally, to serve as the chief energy source for the entire bomb. The consumable pusher makes the bomb more a uranium fission bomb than a hydrogen fusion bomb. It is noteworthy that insiders never used the term hydrogen bomb.[20]

- Finally, the heat for fusion ignition comes not from the primary but from a second fission bomb called the spark plug, embedded in the heart of the secondary. The implosion of the secondary implodes this spark plug, detonating it and igniting fusion in the material around it, but the spark plug then continues to fission in the neutron-rich environment until it is fully consumed, adding significantly to the yield.[21]

The initial impetus behind the two-stage weapon was President Truman's 1950 promise to build a 10-megaton hydrogen superbomb as the U.S. response to the 1949 test of the first Soviet fission bomb. But the resulting invention turned out to be the cheapest and most compact way to build small nuclear bombs as well as large ones, erasing any meaningful distinction between A-bombs and H-bombs, and between boosters and supers. All the best techniques for fission and fusion explosions are incorporated into one all-encompassing, fully scalable design principle. Even six-inch (152 mm) diameter nuclear artillery shells can be two-stage thermonuclears.

In the ensuing fifty years, nobody has come up with a better way to build a nuclear bomb. It is the design of choice for the

United States,

Russia, the

United Kingdom,

China, and

France, the five thermonuclear powers. The other nuclear-armed nations, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea, probably have single-stage weapons, possibly boosted.

[21]

[edit] Interstage

In a two-stage thermonuclear weapon the energy from the primary impacts the secondary. An essential energy transfer modulator called the interstage, between the primary and the secondary, protects the secondary's fusion fuel from heating too quickly, which could cause it to explode in a conventional (and small) heat explosion before the fission and fusion reactions get a chance to start.

There is very little information in the open literature about the mechanism of the interstage. Its first mention in a U.S. government document formally released to the public appears to be a caption in a recent graphic promoting the Reliable Replacement Warhead Program. If built, this new design would replace "toxic, brittle material" and "expensive 'special' material" in the interstage.

[22] This statement suggests the interstage may contain beryllium to moderate the flux of neutrons from the primary, and perhaps something to absorb and re-radiate the x-rays in a particular manner.

[23] There is also some speculation that this interstage material, which may be code-named

FOGBANK might be an

aerogel, possibly doped with beryllium and/or other substances.

[24]

The interstage and the secondary are encased together inside a stainless steel membrane to form the canned subassembly (CSA), an arrangement which has never been depicted in any open-source drawing.

[25] The most detailed illustration of an interstage shows a British thermonuclear weapon with a cluster of items between its primary and a cylindrical secondary. They are labeled "end-cap and neutron focus lens," "reflector/neutron gun carriage," and "reflector wrap." The origin of the drawing, posted on the internet by Greenpeace, is uncertain, and there is no accompanying explanation.

[26]

[edit] Specific designs

While every nuclear weapon design falls into one of the above categories, specific designs have occasionally become the subject of news accounts and public discussion, often with incorrect descriptions about how they work and what they do. Examples:

[edit] Hydrogen bombs

All modern nuclear weapons make some use of D-T fusion. Even pure fission weapons include

neutron generators which are high-voltage vacuum tubes containing trace amounts of tritium and deuterium.

However, in the public perception, hydrogen bombs, or H-bombs, are multi-megaton devices a thousand times more powerful than Hiroshima's Little Boy. Such high-yield bombs are actually two-stage thermonuclears, scaled up to the desired yield, with uranium fission, as usual, providing most of their energy.

The idea of the hydrogen bomb first came to public attention in 1949, when prominent scientists openly recommended against building nuclear bombs more powerful than the standard pure-fission model, on both moral and practical grounds. Their assumption was that critical mass considerations would limit the potential size of fission explosions, but that a fusion explosion could be as large as its supply of fuel, which has no critical mass limit. In 1949, the Soviets exploded their first fission bomb, and in 1950 President Truman ended the H-bomb debate by ordering the Los Alamos designers to build one.

In 1952, the 10.4-megaton

Ivy Mike explosion was announced as the first hydrogen bomb test, reinforcing the idea that hydrogen bombs are a thousand times more powerful than fission bombs.

In 1954,

J. Robert Oppenheimer was labeled a hydrogen bomb opponent. The public did not know there were two kinds of hydrogen bomb (neither of which is accurately described as a hydrogen bomb). On May 23, when his security clearance was revoked, item three of the four public findings against him was "his conduct in the hydrogen bomb program." In 1949, Oppenheimer had supported single-stage fusion-boosted fission bombs, to maximize the explosive power of the arsenal given the trade-off between plutonium and tritium production. He opposed two-stage thermonuclear bombs until 1951, when radiation implosion, which he called "technically sweet", first made them practical. The complexity of his position was not revealed to the public until 1976, nine years after his death.

[27]

When ballistic missiles replaced bombers in the 1960s, most multi-megaton bombs were replaced by missile warheads (also two-stage thermonuclears) scaled down to one megaton or less.

[edit] Alarm Clock/Sloika

The first effort to exploit the symbiotic relationship between fission and fusion was a 1940s design that mixed fission and fusion fuel in alternating thin layers. As a single-stage device, it would have been a cumbersome application of boosted fission. It first became practical when incorporated into the secondary of a two-stage thermonuclear weapon.

[28]

The U.S. name, Alarm Clock, was a nonsense code name. The Russian name for the same design was more descriptive: Sloika (

Russian:

Слойка), a layered pastry cake. A single-stage Soviet Sloika was tested on August 12, 1953. No single-stage U.S. version was tested, but the

Union shot of

Operation Castle, April 26, 1954, was a two-stage thermonuclear code-named Alarm Clock. Its yield, at

Bikini, was 6.9 megatons.

Because the Soviet Sloika test used dry lithium-6 deuteride eight months before the first U.S. test to use it (Castle Bravo, March 1, 1954), it was sometimes claimed that the USSR won the H-bomb race. (The 1952 U.S. Ivy Mike test used cryogenically cooled liquid deuterium as the fusion fuel in the secondary, and employed the D-D fusion reaction.) However, the first Soviet test to use a radiation-imploded secondary, the essential feature of a true H-bomb, was on November 23, 1955, three years after Ivy Mike.

[edit] Clean bombs

Bassoon, the prototype for a 3.5-megaton clean bomb or a 25-megaton

dirty bomb. Dirty version shown here, before its 1956 test.

On March 1, 1954, the largest-ever U.S. nuclear test explosion, the 15-megaton

Bravo shot of Operation Castle at Bikini, delivered a promptly lethal dose of fission-product fallout to more than 6,000 square miles (16,000 km

2) of Pacific Ocean surface.

[29] Radiation injuries to Marshall Islanders and Japanese fishermen made that fact public and revealed the role of fission in hydrogen bombs.

In response to the public alarm over fallout, an effort was made to design a clean multi-megaton weapon, relying almost entirely on fusion. Since the energy produced by the fissioning of

unenriched natural Uranium when utilized as the tamper material in the Secondary and subsequent stages in the Teller-Ulam design, can evidently dwarf the Fusion yield output, as was the case in the

Castle bravo test, and realising that a non

fissionable tamper material is an essential requirement in a 'clean' bomb, it is clear that in such a 'clean' bomb there will now be a relatively massive amount of material that does not undergo any mass-to-energy conversions whatsoever, So for a given weight, 'dirty' weapons with

Fissionable tampers are much lighter than a 'clean' weapon of equal yield. The earliest known incidence of a three-stage device being tested, with the third stage, called the tertiary, being ignited by the secondary, was May 27, 1956 in the Bassoon device. This device was tested in the

Zuni shot of Operation Redwing. This shot utilized non

fissionable tampers, a relatively nuclear inert substitute material such as tungsten or lead was used, its yield was 3.5 megatons, 85% fusion and only 15% fission. The public records for devices that produced the highest proportion of their yield via fusion-only reactions are the 57 megaton,

Tsar bomba at 97% Fusion,

[30] the 9.3 megaton

Hardtack Poplar test at 95.2%,

[31] and the 4.5 megaton

Redwing Navajo test at 95% fusion.

[32]

On July 19 1956, AEC Chairman Lewis Strauss said that the

Redwing Zuni shot clean bomb test "produced much of importance ... from a humanitarian aspect." However, less than two days after this announcement the dirty version of Bassoon, called Bassoon Prime, with a

uranium-238 tamper in place, was tested on a barge off the coast of Bikini Atoll as the

Redwing Tewa shot. The Bassoon Prime produced a 5-megaton yield, of which 87% came from fission. Data obtained from this test, and others culminated in the eventual deployment of the highest yielding US nuclear weapon known, and as a side, the highest

Yield-to-weight weapon ever made a three-stage thermonuclear weapon, with a maximum 'dirty' yield of 25-megatons designated as the

Mark-41 bomb, which was to be carried by U.S. Air Force bombers until it was decommissioned, this weapon was never fully tested.

As such, high-yield clean bombs appear to have been a public relations exercise. The actual deployed weapons were the dirty versions, which maximized yield for the same size device. However Newer 4th and 5th Generation nuclear weapons designs including

Pure fusion weapon and

antimatter catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion like devices

[33] are being studied extensively by the 5 largest nuclear weapon states.

[34][35]

[edit] Cobalt bombs

Main article:

Cobalt bombA fictional doomsday bomb, made popular by

Nevil Shute's 1957

novel, and subsequent 1959 movie,

On the Beach, the cobalt bomb was a hydrogen bomb with a jacket of cobalt metal. The neutron-activated cobalt would supposedly have maximized the environmental damage from radioactive fallout. These bombs were popularized in the 1964 film

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The element added to the bombs is referred to in the film as 'cobalt-thorium G'

Such "salted" weapons were requested by the U.S. Air Force and seriously investigated, possibly built and tested, but not deployed. In the 1964 edition of the DOD/AEC book

The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, a new section titled Radiological Warfare clarified the issue.

[36] Fission products are as deadly as neutron-activated cobalt. The standard high-fission thermonuclear weapon is automatically a weapon of radiological warfare, as dirty as a cobalt bomb.

Initially, gamma radiation from the fission products of an equivalent size fission-fusion-fission bomb are much more intense than

Co-60: 15,000 times more intense at 1 hour; 35 times more intense at 1 week; 5 times more intense at 1 month; and about equal at 6 months. Thereafter fission drops off rapidly so that Co-60 fallout is 8 times more intense than fission at 1 year and 150 times more intense at 5 years. The very long-lived isotopes produced by fission would overtake the

60Co again after about 75 years.

[37]

[edit] Fission-fusion-fission bombs

In 1954, to explain the surprising amount of fission-product fallout produced by hydrogen bombs, Ralph Lapp coined the term fission-fusion-fission to describe a process inside what he called a three-stage thermonuclear weapon. His process explanation was correct, but his choice of terms caused confusion in the open literature. The stages of a nuclear weapon are not fission, fusion, and fission. They are the primary, the secondary, and, in one exceptionally powerful weapon, the tertiary. Each of these stages employs fission, fusion, and fission.

[edit] Neutron bombs

Main article:

Neutron bombA neutron bomb, technically referred to as an enhanced radiation weapon (ERW), is a type of tactical nuclear weapon designed specifically to release a large portion of its energy as energetic neutron radiation. This contrasts with standard thermonuclear weapons, which are designed to capture this intense neutron radiation to increase its overall explosive yield. In terms of yield, ERWs typically produce about one-tenth that of a fission-type atomic weapon. Even with their significantly lower explosive power, ERWs are still capable of much greater destruction than any conventional bomb. Meanwhile, relative to other nuclear weapons, damage is more focused on biological material than on material infrastructure (though extreme blast and heat effects are not eliminated).

Officially known as enhanced radiation weapons, ERWs, they are more accurately described as suppressed yield weapons. When the yield of a nuclear weapon is less than one kiloton, its lethal radius from blast, 700 m (2300 ft), is less than that from its neutron radiation. However, the blast is more than potent enough to destroy most structures, which are less resistant to blast effects than even unprotected human beings. Blast pressures of upwards of 20 PSI are survivable, whereas most buildings will collapse with a pressure of only 5 PSI.

Commonly misconceived as a weapon designed to kill populations and leave infrastructure intact, these bombs (as mentioned above) are still very capable of leveling buildings over a large radius. The intent of their design was to kill tank crews – tanks giving excellent protection against blast and heat, surviving (relatively) very close to a detonation. And with the Soviets' vast tank battalions during the Cold War, this was the perfect weapon to counter them. The neutron radiation could instantly incapacitate a tank crew out to roughly the same distance that the heat and blast would incapacitate an unprotected human (depending on design). The tank chassis would also be rendered highly radioactive (temporarily) preventing its re-use by a fresh crew.

Neutron weapons were also intended for use in other applications, however. For example, they are effective in anti-nuclear defenses – the neutron flux being capable of neutralising an incoming warhead at a greater range than heat or blast. Nuclear warheads are very resistant to physical damage, but are very difficult to harden against extreme neutron flux.

Energy distribution of weapon

| Standard | Enhanced |

| Blast | 50% | 40% |

| Thermal energy | 35% | 25% |

| Instant radiation | 5% | 30% |

| Residual radiation | 10% | 5% |

ERWs were two-stage thermonuclears with all non-essential uranium removed to minimize fission yield. Fusion provided the neutrons. Developed in the 1950s, they were first deployed in the 1970s, by U.S. forces in Europe. The last ones were retired in the 1990s.

A neutron bomb is only feasible if the yield is sufficiently high that efficient fusion stage ignition is possible, and if the yield is low enough that the case thickness will not absorb too many neutrons. This means that neutron bombs have a yield range of 1–10 kilotons, with fission proportion varying from 50% at 1-kiloton to 25% at 10-kilotons (all of which comes from the primary stage). The neutron output per kiloton is then 10–15 times greater than for a pure fission implosion weapon or for a strategic warhead like a

W87 or

W88.

[38]

[edit] Oralloy thermonuclear warheads

In 1999, nuclear weapon design was in the news again, for the first time in decades. In January, the U.S. House of Representatives released the

Cox Report (

Christopher Cox R-CA) which alleged that China had somehow acquired classified information about the U.S. W88 warhead. Nine months later,

Wen Ho Lee, a Taiwanese immigrant working at

Los Alamos, was publicly accused of

spying, arrested, and served nine months in

pre-trial detention, before the case against him was dismissed. It is not clear that there was, in fact, any espionage.

In the course of eighteen months of news coverage, the W88 warhead was described in unusual detail.

The New York Times printed a schematic diagram on its front page.

[39] The most detailed drawing appeared in

A Convenient Spy, the 2001 book on the Wen Ho Lee case by Dan Stober and Ian Hoffman, adapted and shown here with permission.

Designed for use on

Trident II (D-5)

submarine-launched ballistic missiles, the W88 entered service in 1990 and was the last warhead designed for the U.S. arsenal. It has been described as the most advanced, although open literature accounts do not indicate any major design features that were not available to U.S. designers in 1958.

The above diagram shows all the standard features of ballistic missile warheads since the 1960s, with two exceptions that give it a higher yield for its size.

- The outer layer of the secondary, called the "pusher", which serves three functions: heat shield, tamper, and fission fuel, is made of U-235 instead of U-238, hence the name Oralloy (U-235) Thermonuclear. Being fissile, rather than merely fissionable, allows the pusher to fission faster and more completely, increasing yield. This feature is available only to nations with a great wealth of fissile uranium. The United States is estimated to have 500 tons.[citation needed]

- The secondary is located in the wide end of the re-entry cone, where it can be larger, and thus more powerful. The usual arrangement is to put the heavier, denser secondary in the narrow end for greater aerodynamic stability during re-entry from outer space, and to allow more room for a bulky primary in the wider part of the cone. (The W87 warhead drawing in the previous section[clarification needed] shows the usual arrangement.) Because of this new geometry, the W88 primary uses compact conventional high explosives (CHE) to save space,[40] rather than the more usual, and bulky but safer, insensitive high explosives (IHE). The re-entry cone probably has ballast in the nose for aerodynamic stability.[41]

The alternating layers of fission and fusion material in the secondary are an application of the Alarm Clock/Sloika principle.

[edit] Reliable replacement warhead

The United States has not produced any nuclear warheads since 1989, when the

Rocky Flats pit production plant, near

Boulder, Colorado, was shut down for environmental reasons. With the end of the

Cold War two years later, the production line was idled except for inspection and maintenance functions.

The

National Nuclear Security Administration, the latest successor for nuclear weapons to the

Atomic Energy Commission and the

Department of Energy, has proposed building a new pit facility and starting the production line for a new warhead called the

Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW).

[42] Two advertised safety improvements of the RRW would be a return to the use of "insensitive high explosives which are far less susceptible to accidental detonation", and the elimination of "certain hazardous materials, such as

beryllium, that are harmful to people and the environment."

[43] Since the new warhead must not require any nuclear testing, it could not use a new design with untested concepts.

[edit] Weapon design laboratories

All the nuclear weapon design innovations discussed in this article originated from the following three labs in the manner described. Other nuclear weapon design labs in other countries duplicated those design innovations independently, reverse-engineered them from fallout analysis, or acquired them by espionage.

[44]

[edit] Berkeley

The first systematic exploration of nuclear weapon design concepts took place in mid-1942 at the

University of California, Berkeley. Important early discoveries had been made at the adjacent

Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, such as the 1940 cyclotron-made production and isolation of plutonium. A Berkeley professor,

J. Robert Oppenheimer, had just been hired to run the nation's secret bomb design effort. His first act was to convene the 1942 summer conference.

By the time he moved his operation to the new secret town of Los Alamos, New Mexico, in the spring of 1943, the accumulated wisdom on nuclear weapon design consisted of five lectures by Berkeley professor

Robert Serber, transcribed and distributed as the

Los Alamos Primer. The Primer addressed fission energy,

neutron production and

capture,

nuclear chain reactions,

critical mass, tampers, predetonation, and three methods of assembling a bomb: gun assembly, implosion, and "autocatalytic methods," the one approach that turned out to be a dead end.

[edit] Los Alamos

At Los Alamos, it was found in April 1944 by

Emilio G. Segrè that the proposed

Thin Man Gun assembly type bomb would not work for plutonium because of predetonation problems caused by Pu-240 impurities. So Fat Man, the implosion-type bomb, was given high priority as the only option for plutonium. The Berkeley discussions had generated theoretical estimates of critical mass, but nothing precise. The main wartime job at Los Alamos was the experimental determination of critical mass, which had to wait until sufficient amounts of fissile material arrived from the production plants: uranium from

Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and plutonium from the

Hanford site in Washington.

In 1945, using the results of critical mass experiments, Los Alamos technicians fabricated and assembled components for four bombs: the

Trinity Gadget, Little Boy, Fat Man, and an unused spare Fat Man. After the war, those who could, including Oppenheimer, returned to university teaching positions. Those who remained worked on levitated and hollow pits and conducted weapon effects tests such as

Crossroads Able and Baker at

Bikini Atoll in 1946.

All of the essential ideas for incorporating fusion into nuclear weapons originated at Los Alamos between 1946 and 1952. After the

Teller-Ulam radiation implosion breakthrough of 1951, the technical implications and possibilities were fully explored, but ideas not directly relevant to making the largest possible bombs for long-range Air Force bombers were shelved.

Because of Oppenheimer's initial position in the H-bomb debate, in opposition to large thermonuclear weapons, and the assumption that he still had influence over Los Alamos despite his departure, political allies of

Edward Teller decided he needed his own laboratory in order to pursue H-bombs. By the time it was opened in 1952, in

Livermore, California, Los Alamos had finished the job Livermore was designed to do.

[edit] Livermore

With its original mission no longer available, the Livermore lab tried radical new designs, that failed. Its first three nuclear tests were

fizzles: in 1953, two single-stage

fission devices with uranium hydride pits, and in 1954, a two-stage thermonuclear device in which the secondary heated up prematurely, too fast for radiation implosion to work properly.

Shifting gears, Livermore settled for taking ideas Los Alamos had shelved and developing them for the Army and Navy. This led Livermore to specialize in small-diameter tactical weapons, particularly ones using two-point implosion systems, such as the Swan. Small-diameter tactical weapons became primaries for small-diameter secondaries. Around 1960, when the superpower arms race became a ballistic missile race, Livermore warheads were more useful than the large, heavy Los Alamos warheads. Los Alamos warheads were used on the first

intermediate-range ballistic missiles, IRBMs, but smaller Livermore warheads were used on the first

intercontinental ballistic missiles, ICBMs, and

submarine-launched ballistic missiles, SLBMs, as well as on the first

multiple warhead systems on such missiles.

[45]

In 1957 and 1958 both labs built and tested as many designs as possible, in anticipation that a planned 1958 test ban might become permanent. By the time testing resumed in 1961 the two labs had become duplicates of each other, and design jobs were assigned more on workload considerations than lab specialty. Some designs were horse-traded. For example, the

W38 warhead for the

Titan I missile started out as a Livermore project, was given to Los Alamos when it became the

Atlas missile warhead, and in 1959 was given back to Livermore, in trade for the

W54 Davy Crockett warhead, which went from Livermore to Los Alamos.

The period of real innovation was ending by then, anyway. Warhead designs after 1960 took on the character of model changes, with every new missile getting a new warhead for marketing reasons. The chief substantive change involved packing more fissile uranium into the secondary, as it became available with continued

uranium enrichment and the dismantlement of the large high-yield bombs.

[edit] Explosive testing

Nuclear weapons are in large part designed by trial and error. The trial often involves test explosion of a prototype.

In a nuclear explosion, a large number of discrete events, with various probabilities, aggregate into short-lived, chaotic energy flows inside the device casing. Complex mathematical models are required to approximate the processes, and in the 1950s there were no computers powerful enough to run them properly. Even today's computers and simulation software are not adequate.

[46]

It was easy enough to design reliable weapons for the stockpile. If the prototype worked, it could be weaponized and mass produced.

It was much more difficult to understand how it worked or why it failed. Designers gathered as much data as possible during the explosion, before the device destroyed itself, and used the data to calibrate their models, often by inserting

fudge factors into equations to make the simulations match experimental results. They also analyzed the weapon debris in fallout to see how much of a potential nuclear reaction had taken place.

[edit] Light pipes

An important tool for test analysis was the diagnostic light pipe. A probe inside a test device could transmit information by heating a plate of metal to incandescence, an event that could be recorded at the far end of a long, very straight pipe.

The picture below shows the Shrimp device, detonated on March 1, 1954 at Bikini, as the

Castle Bravo test. Its 15-megaton explosion was the largest ever by the United States. The silhouette of a man is shown for scale. The device is supported from below, at the ends. The pipes going into the shot cab ceiling, which appear to be supports, are diagnostic light pipes. The eight pipes at the right end (1) sent information about the detonation of the primary. Two in the middle (2) marked the time when x-radiation from the primary reached the radiation channel around the secondary. The last two pipes (3) noted the time radiation reached the far end of the radiation channel, the difference between (2) and (3) being the radiation transit time for the channel.

[47]

From the shot cab, the pipes turned horizontal and traveled 7500 ft (2.3 km), along a causeway built on the Bikini reef, to a remote-controlled data collection bunker on Namu Island.

While x-rays would normally travel at the speed of light through a low density material like the plastic foam channel filler between (2) and (3), the intensity of radiation from the exploding primary created a relatively opaque radiation front in the channel filler which acted like a slow-moving logjam to retard the passage of radiant energy. While the secondary is being compressed via radiation induced ablation, neutrons from the primary catch up with the x-rays, penetrate into the secondary and start breeding tritium with the third reaction noted in the first section above. This Li-6 + n reaction is exothermic, producing 5 MeV per event. The spark plug is not yet compressed and thus is not critical, so there won't be significant fission or fusion. But if enough neutrons arrive before implosion of the secondary is complete, the crucial temperature difference will be degraded. This is the reported cause of failure for Livermore's first thermonuclear design, the Morgenstern device, tested as

Castle Koon, April 7, 1954.

These timing issues are measured by light-pipe data. The mathematical simulations which they calibrate are called radiation flow hydrodynamics codes, or channel codes. They are used to predict the effect of future design modifications.

It is not clear from the public record how successful the Shrimp light pipes were. The data bunker was far enough back to remain outside the mile-wide crater, but the 15-megaton blast, two and a half times greater than expected, breached the bunker by blowing its 20-ton door off the hinges and across the inside of the bunker. (The nearest people were twenty miles (32 km) farther away, in a bunker that survived intact.)

[48]

[edit] Fallout analysis

The most interesting data from Castle Bravo came from radio-chemical analysis of weapon debris in fallout. Because of a shortage of enriched lithium-6, 60% of the lithium in the Shrimp secondary was ordinary lithium-7, which doesn't breed tritium as easily as lithium-6 does. But it does breed lithium-6 as the product of an (n, 2n) reaction (one neutron in, two neutrons out), a known fact, but with unknown probability. The probability turned out to be high.

Fallout analysis revealed to designers that, with the (n, 2n) reaction, the Shrimp secondary effectively had two and half times as much lithium-6 as expected. The tritium, the fusion yield, the neutrons, and the fission yield were all increased accordingly.

[49]

As noted above, Bravo's fallout analysis also told the outside world, for the first time, that thermonuclear bombs are more fission devices than fusion devices. A Japanese fishing boat, the

Lucky Dragon, sailed home with enough fallout on its decks to allow scientists in Japan and elsewhere to determine, and announce, that most of the fallout had come from the fission of U-238 by fusion-produced 14 MeV neutrons.

[edit] Underground testing

Subsidence Craters at Yucca Flat, Nevada Test Site.

The global alarm over radioactive fallout, which began with the Castle Bravo event, eventually drove nuclear testing underground. The last U.S. above-ground test took place at

Johnston Island on November 4, 1962. During the next three decades, until September 23, 1992, the United States conducted an average of 2.4 underground nuclear explosions per month, all but a few at the

Nevada Test Site (NTS) northwest of Las Vegas.

The

Yucca Flat section of the NTS is covered with subsidence craters resulting from the collapse of terrain over radioactive underground caverns created by nuclear explosions (see photo).

After the 1974

Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), which limited underground explosions to 150 kilotons or less, warheads like the half-megaton W88 had to be tested at less than full yield. Since the primary must be detonated at full yield in order to generate data about the implosion of the secondary, the reduction in yield had to come from the secondary. Replacing much of the lithium-6 deuteride fusion fuel with lithium-7 hydride limited the tritium available for fusion, and thus the overall yield, without changing the dynamics of the implosion. The functioning of the device could be evaluated using light pipes, other sensing devices, and analysis of trapped weapon debris. The full yield of the stockpiled weapon could be calculated by extrapolation.

[edit] Production facilities

When two-stage weapons became standard in the early 1950s, weapon design determined the layout of the new, widely dispersed U.S. production facilities, and vice versa.

Because primaries tend to be bulky, especially in diameter, plutonium is the fissile material of choice for pits, with beryllium reflectors. It has a smaller critical mass than uranium. The

Rocky Flats plant near Boulder, Colorado, was built in 1952 for pit production and consequently became the plutonium and beryllium fabrication facility.

The Y-12 plant in

Oak Ridge,

Tennessee, where

mass spectrometers called

Calutrons had enriched uranium for the

Manhattan Project, was redesigned to make secondaries. Fissile U-235 makes the best spark plugs because its critical mass is larger, especially in the cylindrical shape of early thermonuclear secondaries. Early experiments used the two fissile materials in combination, as composite Pu-Oy pits and spark plugs, but for mass production, it was easier to let the factories specialize: plutonium pits in primaries, uranium spark plugs and pushers in secondaries.

Y-12 made lithium-6 deuteride fusion fuel and U-238 parts, the other two ingredients of secondaries.

The

Savannah River plant in

Aiken,

South Carolina, also built in 1952, operated

nuclear reactors which converted U-238 into Pu-239 for pits, and converted lithium-6 (produced at Y-12) into tritium for booster gas. Since its reactors were moderated with heavy water, deuterium oxide, it also made deuterium for booster gas and for Y-12 to use in making lithium-6 deuteride.

[edit] Warhead design safety

Because even low-yield nuclear warheads have astounding destructive power, weapon designers have always recognised the need to incorporate mechanisms and associated procedures intended to prevent accidental detonation.

A diagram of the

Green Grass warhead's steel ball safety device, shown left, filled (safe) and right, empty (live). The steel balls were emptied into a hopper underneath the aircraft before flight, and could be re-inserted using a funnel by rotating the bomb on its trolley and raising the hopper.

- Gun-type weapons

It is inherently dangerous to have a weapon containing a quantity and shape of fissile material which can form a critical mass through a relatively simple accident. Because of this danger, the propellant in Little Boy (four bags of

cordite) was inserted into the bomb in flight, shortly after takeoff on August 6, 1945. This was the first time a gun-type nuclear weapon had ever been fully assembled.

If the weapon falls into water, the

moderating effect of the

water can also cause a

criticality accident, even without the weapon being physically damaged. Similarly, a fire caused by an aircraft crashing could easily ignite the propellant, with catastrophic results. Gun-type weapons have always been inherently unsafe.

- In-flight pit insertion

Neither of these effects is likely with implosion weapons since there is normally insufficient fissile material to form a critical mass without the correct detonation of the lenses. However, the earliest implosion weapons had pits so close to criticality that accidental detonation with some nuclear yield was a concern.

On August 9, 1945, Fat Man was loaded onto its airplane fully assembled, but later, when levitated pits made a space between the pit and the tamper, it was feasible to use in-flight pit insertion. The bomber would take off with no fissile material in the bomb. Some older implosion-type weapons, such as the US

Mark 4 and

Mark 5, used this system.

In-flight pit insertion will not work with a hollow pit in contact with its tamper.

- Steel ball safety method

As shown in the diagram above, one method used to decrease the likelihood of accidental detonation employed

metal balls. The balls were emptied into the pit: this prevented detonation by increasing the density of the hollow pit, thereby preventing symmetrical implosion in the event of an accident. This design was used in the Green Grass weapon, also known as the Interim Megaton Weapon, which was used in the

Violet Club and

Yellow Sun Mk.1 bombs.

- Chain safety method

Alternatively, the pit can be "safed" by having its normally hollow core filled with an inert material such as a fine metal chain, possibly made of

cadmium to absorb neutrons. While the chain is in the center of the pit, the pit can not be compressed into an appropriate shape to fission; when the weapon is to be armed, the chain is removed. Similarly, although a serious fire could detonate the explosives, destroying the pit and spreading plutonium to contaminate the surroundings as has happened in

several weapons accidents, it could not cause a nuclear explosion.

- Wire safety method

The US

W47 warhead used in

Polaris A1 and

Polaris A2 had a safety device consisting of a

boron-coated wire inserted into the hollow pit at manufacture. The warhead was armed by withdrawing the wire onto a spool driven by an electric motor. Once withdrawn the wire could not be re-inserted.

[50]

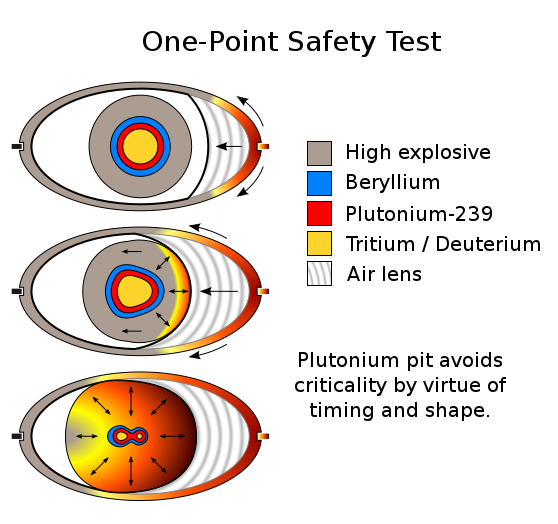

- One-point safety

While the firing of one detonator out of many will not cause a hollow pit to go critical, especially a low-mass hollow pit that requires boosting, the introduction of two-point implosion systems made that possibility a real concern.

In a two-point system, if one detonator fires, one entire hemisphere of the pit will implode as designed. The high-explosive charge surrounding the other hemisphere will explode progressively, from the equator toward the opposite pole. Ideally, this will pinch the equator and squeeze the second hemisphere away from the first, like toothpaste in a tube. By the time the explosion envelops it, its implosion will be separated both in time and space from the implosion of the first hemisphere. The resulting dumbbell shape, with each end reaching maximum density at a different time, may not become critical.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to tell on the drawing board how this will play out. Nor is it possible using a dummy pit of U-238 and high-speed x-ray cameras, although such tests are helpful. For final determination, a test needs to be made with real fissile material. Consequently, starting in 1957, a year after Swan, both labs began one-point safety tests.

Out of 25 one-point safety tests conducted in 1957 and 1958, seven had zero or slight nuclear yield (success), three had high yields of 300 t to 500 t (severe failure), and the rest had unacceptable yields between those extremes.

Of particular concern was Livermore's W47 warhead for the Polaris submarine missile. The last test before the 1958 moratorium was a one-point test of the W47 primary, which had an unacceptably high nuclear yield of 400 lb (180 kg) of TNT equivalent (Hardtack II Titania). With the test moratorium in force, there was no way to refine the design and make it inherently one-point safe. Los Alamos had a suitable primary that was one-point safe, but rather than share with Los Alamos the credit for designing the first SLBM warhead, Livermore chose to use mechanical safing on its own inherently unsafe primary. The wire safety scheme described above was the result.

[51]

It turns out that the

W47 may have been safer than anticipated. The wire-safety system may have rendered most of the warheads "duds," unable to fire when detonated.

[51]

When testing resumed in 1961, and continued for three decades, there was sufficient time to make all warhead designs inherently one-point safe, without need for mechanical safing.

- Strong link weak link

A strong link/weak link and exclusion zone nuclear detonation mechanism is a form of automatic

safety interlock.

- Permissive Action Links

In addition to the above steps to reduce the probability of a nuclear detonation arising from a single fault, locking mechanisms referred to by NATO states as Permissive Action Links are sometimes attached to the control mechanisms for nuclear warheads. Permissive Action Links act solely to prevent the unauthorised use of a nuclear weapon.

[edit] References

[edit] Bibliography

- Cohen, Sam, The Truth About the Neutron Bomb: The Inventor of the Bomb Speaks Out, William Morrow & Co., 1983

- Coster-Mullen, John, "Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man", Self-Published, 2011

- Glasstone, Samuel and Dolan, Philip J., The Effects of Nuclear Weapons (third edition) (hosted at the Trinity Atomic Web Site), U.S. Government Printing Office, 1977. PDF Version

- Grace, S. Charles, Nuclear Weapons: Principles, Effects and Survivability (Land Warfare: Brassey's New Battlefield Weapons Systems and Technology, vol 10)

- Hansen, Chuck, The Swords of Armageddon: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945, October 1995, Chucklea Productions, eight volumes (CD-ROM), two thousand pages.

- The Effects of Nuclear War, Office of Technology Assessment (May 1979).

- Rhodes, Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon and Schuster, New York, (1986 ISBN 978-0-684-81378-3)

- Rhodes, Richard. Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Simon and Schuster, New York, (1995 ISBN 978-0-684-82414-7)

- Smyth, Henry DeWolf, Atomic Energy for Military Purposes, Princeton University Press, 1945. (see: Smyth Report)

- ^ The physics package is the nuclear explosive module inside the bomb casing, missile warhead, or artillery shell, etc., which delivers the weapon to its target. While photographs of weapon casings are common, photographs of the physics package are quite rare, even for the oldest and crudest nuclear weapons. For a photograph of a modern physics package see W80.

- ^ Life Editors (1961), "To the Outside World, a Superbomb more Bluff than Bang", Life (New York) (Vol. 51, No. 19, November 10, 1961): 34–37, retrieved 2010-06-28. Article on the Soviet Tsar Bomba test. Because explosions are spherical in shape and targets are spread out on the relatively flat surface of the earth, numerous smaller weapons cause more destruction. From page 35: ". . .five five-megaton weapons would demolish a greater area than a single 50-megatonner."

- ^ The United States and the Soviet Union were the only nations to build large nuclear arsenals with every possible type of nuclear weapon. The U.S. had a four-year head start and was the first to produce fissile material and fission weapons, all in 1945. The only Soviet claim for a design first was the Joe 4 detonation on August 12, 1953, said to be the first deliverable hydrogen bomb. However, as Herbert York first revealed in The Advisors: Oppenheimer, Teller and the Superbomb (W.H. Freeman, 1976), it was not a true hydrogen bomb (it was a boosted fission weapon of the Sloika/Alarm Clock type, not a two-stage thermonuclear). Soviet dates for the essential elements of warhead miniaturization – boosted, hollow-pit, two-point, air lens primaries – are not available in the open literature, but the larger size of Soviet ballistic missiles is often explained as evidence of an initial Soviet difficulty in miniaturizing warheads.

- ^ fr 971324, Caisse Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique (National Fund for Scientific Research), "Perfectionnements aux charges explosives (Improvements to explosive charges)", published 16 January 1951, issued 12 July 1950.